"The first time I visited a hospital, I was 11 years old. Despite my mother having been hospitalized several times before, my parents tried to keep my sister and me away for as long as possible. But that day, there was going to be the hospital admission that would mark the end of all admissions: my mother was receiving a new kidney.

I wasn’t bothered by the cacophony of alarms, beeps, and cries. The only thing I could see was my mother. The transplant was successful, but unbeknownst to everyone, it was only half the battle. She had complications after the surgery. This, coupled with her already complex medical history, meant that many more hospital admissions awaited us.

It was and still is difficult to see my best friend suffer, to help her organize an ever-growing number of pills. There’s a saying my mother used when my sister and I were sick; she would gently hold our hands and say, ‘I wish it were me instead of you.’ Only now, when I hold her hands in mine, do I know what she meant.

All this to say that I am no stranger to pain, to sorrow, and to loneliness, as are we all. However, I believe that a life worth living is not one without suffering. In fact, I am grateful for this hardship and the ones that accompanied it.

What if I told you that you would live this life again, experiencing every pain, joy, and insignificant moment for all eternity? Would you curse the universe or rejoice?

Nietzsche posed the same question to demonstrate amor fati, or love of fate, where one embraces everything life has to offer, including suffering (1). The titular Zarathustra is the quintessential example of one who embodies amor fati. In his wanderings, Zarathustra climbs a mountain and finds a great sea of pain before him. He is understandably discouraged, but offers this encouragement: ‘Where do the highest mountains come from? I once asked. Then I learned that they come from the sea’ (2).

Zarathustra reminds himself that the peaks of greatness are forged from the seas of pain, and he embraces the cycle. In the end, it is revealed that Zarathustra ‘will return eternally to this...same life’ and he rejoices in this. This is what Nietzsche called the formula for greatness: ‘the fact that a man wants nothing to be different for all eternity’ (3).

In his autobiography, actor and comedian Stephen Colbert reflects on the greatest tragedy of his life, a plane crash that caused the death of his father and two brothers. He writes, ‘I love the thing that I most wish had not happened’ (4). He goes on to explain that, from his loss, he also received the gift of a more complete humanity, which allowed him to connect and love more deeply. ‘If you are grateful for your life,’ Colbert says, ‘you must be grateful for all of it’ – Amor fati (5).

Viktor Frankl, a psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, famously wrote, ‘If there is meaning in life, there must be meaning in suffering’ (6). A life worth living is one with the capacity to consecrate suffering into a deeper human connection – a deeper understanding, sweetness, forgiveness, humility, and love. A life where, if you had to return eternally to this same fate, you would do so with gratitude.

It was suffering that deepened my capacity to love and inspired my vocation in public health. For this, I am grateful and blessed. If suffering in the past meant that I could help people like my mother in the future, then, in the words of Anne Lamott, hallelujah anyway (7).

Hospital for the Spirit:

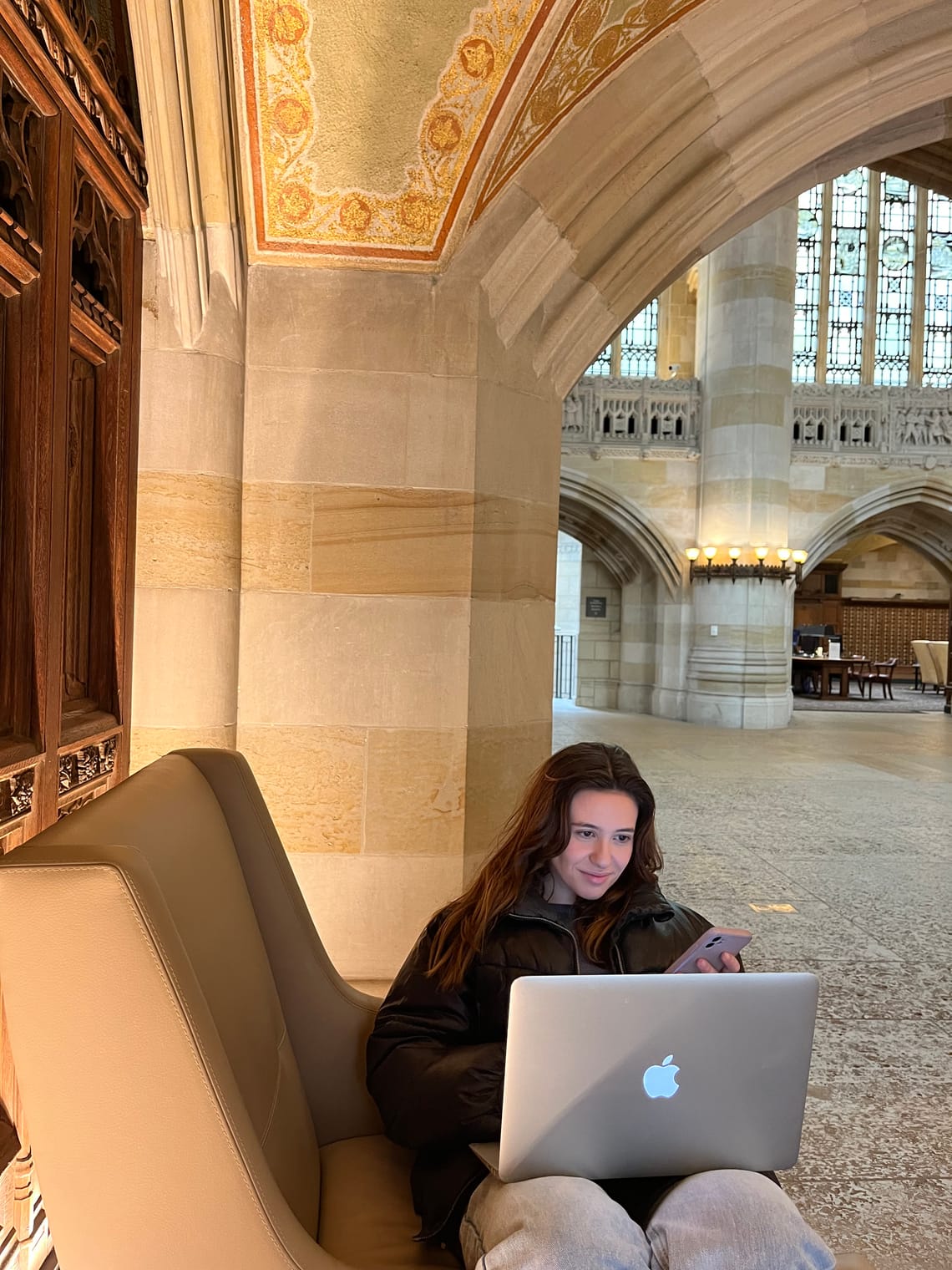

What is it like to enter a hospital? As someone who has visited many, this is not an easy question to answer. Hospital corridors are places where people rejoice, cry, hope, and pray. This is what it feels like in a place of healing. Among these feelings, I wonder if one of them is that of welcome.

Before the modern hospital became a place for physical healing, it was a place for spiritual healing. The word ‘hospital’ derives from the Latin term ‘hospes,’ which means guest, stranger, or foreigner. This origin harks back to medieval times when hospitals had various charitable functions (8). Hospitals could be places of healing for the sick, care for the dying, and lodging for the wandering pilgrim (9). The multifunctional use of the medieval hospital reflected those who managed them – devout monks and nuns.

If a hospital is a place of hospitality, then the monks and nuns who managed it – the modern doctors – were the hosts. Being a host was a sacred duty. The dynamic of being simultaneously host and pilgrim ties to the command to love your neighbor as yourself (Mark 12:31 NIV) (10). There are many instances where Jesus embodies both roles, offering and receiving hospitality from others (14). At one point, showing love for the sick is equated to showing love for Christ (Matthew 25:43 NIV) (11). Broadly speaking, the relationship between God and man is a reciprocal role of host and guest. Men are called to welcome God into their hearts, and God welcomes men to accept His refuge and the gift of salvation. We also exist in a reciprocal and indistinct cycle of host and guest, caregiver and cared-for, in everyday life. Author and physician Victoria Sweet alludes to this relationship in ‘God’s Hotel’ saying, ‘In the hospital, every guest will surely become an invitee; every doctor, a patient’ (pg. 152) (12).

What makes a place worthy of pilgrimage? One answer is the reputation for miraculous healing that many pilgrimage sites share. Most medieval and contemporary pilgrims undertake journeys with the goal that their ailment will be healed (13). Hospitals are also places with established reputations for healing, where the sick travel to be healed in almost miraculous ways. In this way, patients require faith in medicine, in a doctor, or in healing. This dynamic blurs the roles of religious pilgrim and patient.

Fragments of medieval hospitals remain, with integrated chapels and chaplains administering spiritual care to patients. However, doctors still occupy the historical role of spiritual hosts. When a patient engages in a doctor-patient relationship, they ask to enter a partnership where they share their vulnerabilities, hopes, pains, and priorities. Asking ‘will you be my doctor?’ means asking, ‘will you host me? Will you be my neighbor?’”